Anglo-Saxon Art

The shorthand often use for the period between the end of Roman Britain and the Norman conquest is the “Dark Ages”. And whilst there are significantly fewer written sources in this period, the art of the period suggests it was anything but dim, dark or uncultured.

Anglo Saxon art can be divided into two phases; one occurring before the late 9th century Viking invasion and one after. It can also be divided by its producers: monks on the one hand, and Angles and Saxons artisans themselves. It embraces both pre-Christian Scandinavian / Germanic motifs and, following the conversion of the British Isles, Christian iconography. This article focuses on the art produced before the Viking invasion.

Pagan Period

Pagan Anglo-Saxon art (fifth-sixth centuries AD) roughly coincides with with a type of art known as Style I. It is seen in decorations on weapons, jewellery, pottery, and other small personal belongings. There is nothing monumental, no large sculptures or paintings. The metalwork, however, is often intricate and elaborate, fashioned in gold, silver, or gilt. It is often boldly jewelled with garnets, coloured glass and shell.

The dense animal patterns that cover many Anglo-Saxon objects, from this period, are not just pretty decoration, they have multi-layered symbolic meanings and tell stories. Anglo-Saxons, who had a love of riddles and puzzles of all kinds, would have been able to ‘read’ the stories embedded in the decoration.

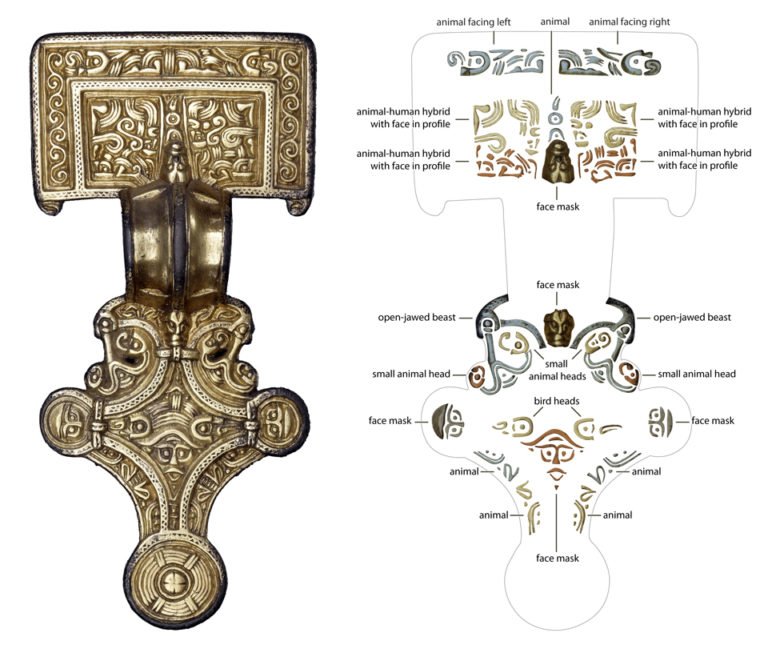

One of the most exquisite examples of Style I animal art is a silver-gilt square-headed brooch from a female grave on the Isle of Wight, made by an Anglo-Saxon artisan. Its surface is covered with at least 24 different beasts: a mix of birds’ heads, human masks, animals and hybrids. Some of them are quite clear, like the faces in the circular lobes projecting from the bottom of the brooch. Others are harder to spot, such as the faces in profile that only emerge when the brooch is turned upside-down. Some of the images can be read in multiple ways, and this ambiguity is central to Style I art.

© The British Museum

Once the creatures on the brooch have been identified, the meaning can be decoded. In the lozenge-shaped field at the foot of the brooch is a bearded face with a helmet underneath two birds that may represent the Germanic god Woden with his two companion ravens. The image of a god alongside other powerful animals may have offered symbolic protection to the wearer like a talisman or amulet.

Where the artisan craftsmen used the cloisonné technique (see below), Anglo-Saxon jewellers attained a skill unsurpassed in the pagan Germanic world. They also made dexterous use of filigree and Niello (a black mixture of sulphur, copper, silver and lead, used as an inlay on engraved metal). Metalworkers of this pagan period also produced accurate enamelling in the Celtic style deriving from Celtic influences that preceded or existed along with Saxon conquests.

Three cloisonné birds' heads with cabochon garnet eyes, arranged in the form of a triskele, radiate from a central garnet ring. King's Field, Faversham, Kent.

© British Museum

Gold tear-shaped pendant set with garnets and blue glass and with filigree rim. King's Field, Faversham, Kent.

© British Museum

One of the most important discoveries of Anglo-Saxon "Art".

Christian Period

Christian Anglo-Saxon art (seventh to eleventh century AD) begins at the same time as we start to see a type of art known as Style II.

This later style included animals, but in a more fluid and graceful style. They still writhe and interlace together and require patient untangling. The great gold buckle from Sutton Hoo is decorated in this style. From the thicket of interlace that fills the buckle’s surface 13 different animals emerge (see below). These animals are easier to spot: the ring-and-dot eyes, the birds’ hooked beaks, and the four-toed feet of the animals are good starting points. At the tip of the buckle, two animals grip a small dog-like creature in their jaws and on the circular plate, two snakes intertwine and bite their own bodies. Such designs reveal the continuing importance of the natural world.

© The British Museum

The period also saw the start of Christian iconography being included, by artisans, in art work. A rare example is the beautiful gold and garnet cross, found on the breast of a teenage girl buried lying on her own bed, between 650 and 680 AD, near Cambridge. Her burial is not wholly Christian though, as her grave included pagan style grave offerings which were probably also treasured possessions, including gold and garnet pins, an iron knife, glass beads and a chain, which probably hung from her belt.

Garnet and gold cross discovered in 2011 on the body of a teenage girl buried near Cambridge

As well as fine metalwork, this later period also yields (Christian) illuminated manuscripts, created by monks in the monasteries that were founding after 600 AD; and sculpture in stone, in and around the new Anglo-Saxon churches.

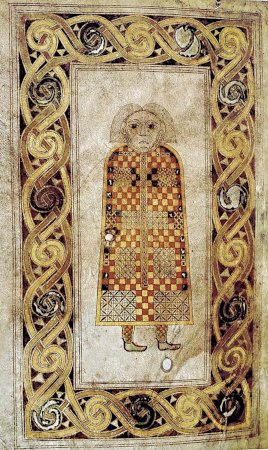

The earliest manuscript painting, from late seventh-century Northumbria, decorates the Book of Durrow (Trinity College, Dublin); its style is hard and metallic, and embodies millefiori panels, Ribbon Style animals, and Celtic spiral scrolls.

On the other hand, the Lindisfarne Gospels (British Museum), c. 700 AD, is illustrated with Evangelist portraits of Italian origin and magnificent full pages of minutely intricate, carpetlike abstract ornament of Celtic and Saxon origin.

By the 9th century, Anglo Saxon missions were reaching as far as the Carolingian Empire and exported their style of illuminating the manuscripts with them.

Lindisfarne gospels.

© British Library

Book of Durrow.

© The Library of Trinity College Dublin

In the heart of Mercia, the church of St Mary and St Hardulph, in Breedon on the Hill, includes impressive examples of Anglo-Saxon stone carvings. Set in the bell-ringing chamber of the church tower is perhaps the most famous piece of Breedon sculpture, depicting the Angel Gabriel. Many other carvings exist, some using naturalistic elements as well others, depicting saints and bible stories.

A narrow frieze, 7 inches wide, running the full width of the chancel consisting of a conventionalised vine-scroll with single and trefoiled leaves.

© http://greatenglishchurches.co.uk/

The Breedon “Angel”.

© thiswasleicestershire.co.uk

For a short survey of stone sculpture throughout the Anglo-Saxon period, there’s a link below to an article from the British Academy:

This short article only begins to uncover the depth and breadth of Anglo-Saxon art work. For a more complete survey, the documentary below is a great introduction:

A video from Dr Janina Ramirez entitled: "The Treasures of the Anglo-Saxons".